SUNDARABANS, WEST BENGAL, INDIA, 8 JANUARY 2016: Mahammad Ali Molla, 60, has been blind for the last 14 years. He goes for tea every day and his grandson accompanies him on the 2 kilometer walk to the local market. He also assists him as he drinks and eats when he is not at school. Mahammad developed a problem with his eyes when tree sap entered in them while working as an agricultural labourer. He could not access eye treatment and as his eyes were neglected he developed corneal ulcers. He sought medical help from local quacks who took his money but destroyed his one eye and damaged the other with their ill-advised treatment techniques. He received further surgery from Kolkata Medical college but they could not save his remaining vision. He spent 30 000 rupees on that trip to Kolkata and it is likely most of that money went to living away from his home while undergoing treatment as well as paying unscrupulous middle men. Mahammad is supported by his wife Samiran Molla, 55, who has had to shoulder the financial burden of raising their 5 children. They survive today with meagre fishing income and by her eating with one son and Mahammad eating with the other. It is likely Mahammad's blindness could have been prevented by access to qualified eye care but his remote location and lack of local facilities as well as his state of poverty prevented access to correct treatment. This story is not uncommon in the more remote parts of India where remote communities are encumbered by a lack of quality eye care at hand and poverty makes travel and care inaccesable. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Reportage for National Geographic Magazine.)

SUNDARABANS, WEST BENGAL, INDIA, 8 JANUARY 2016: Mahammad Ali Molla, 60, has been blind for the last 14 years. He developed a problem with his eyes when tree sap entered in them while working as an agricultural labourer. He could not access eye treatment and as his eyes were neglected he developed corneal ulcers. He sought medical help from local quacks who took his money but destroyed his one eye and damaged the other with their ill-advised treatment techniques. He received further surgery from Kolkata Medical college but they could not save his remaining vision. He spent 30 000 rupees on that trip to Kolkata and it is likely most of that money went to living away from his home while undergoing treatment as well as paying unscrupulous middle men. Mahammad is supported by his wife Samiran Molla, 55, who has had to shoulder the financial burden of raising their 5 children. They survive today with meagre fishing income and by her eating with one son and Mahammad eating with the other. It is likely Mahammad's blindness could have been prevented by access to qualified eye care but his remote location and lack of local facilities as well as his state of poverty prevented access to correct treatment. This story is not uncommon in the more remote parts of India where remote communities are encumbered by a lack of quality eye care at hand and poverty makes travel and care inaccesable. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Reportage for National Geographic Magazine.)

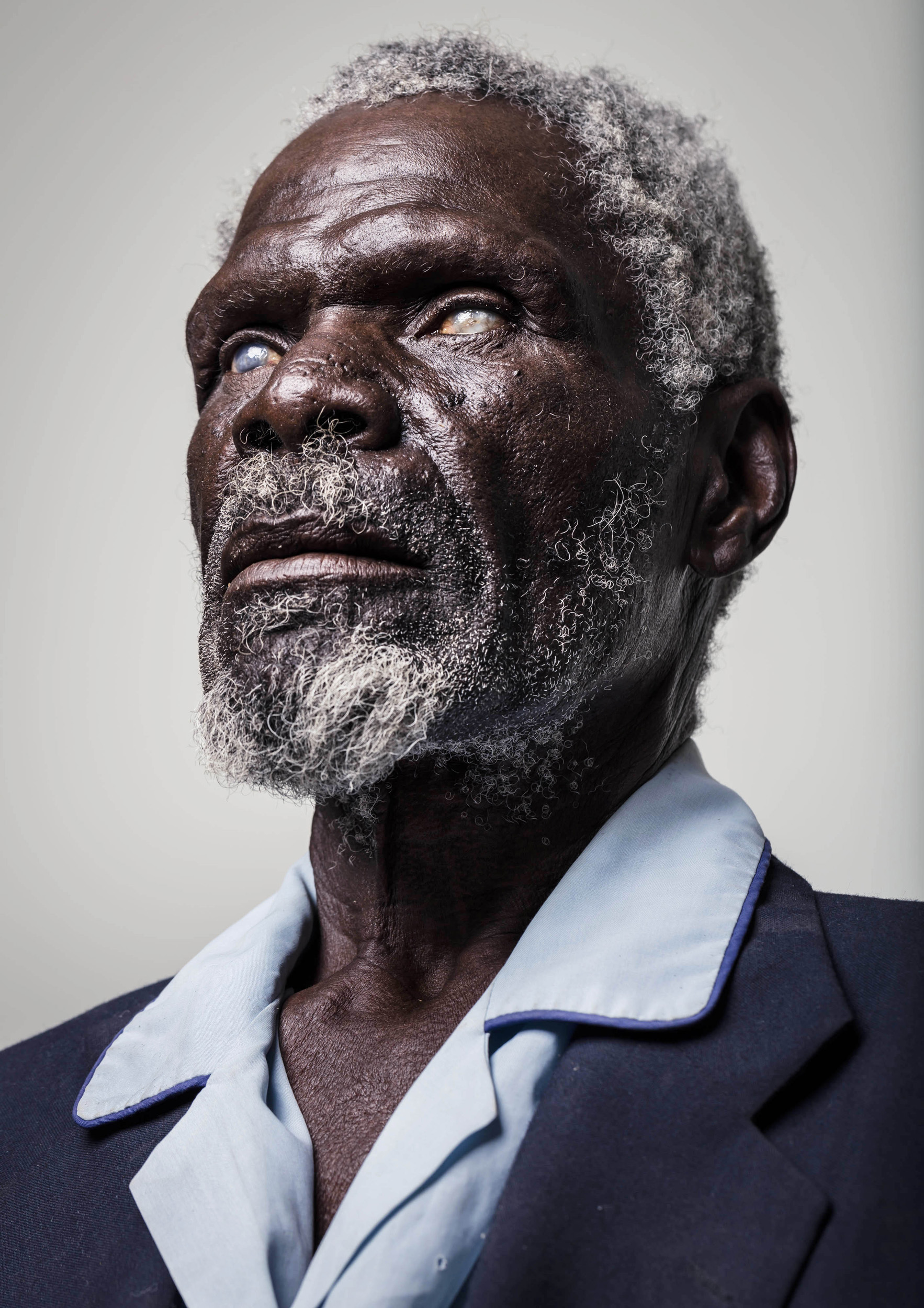

OMARURU, NAMIBIA, 5 November 2015: Gerd Gamanab, 67, is a completely sightless man hoping for a miracle at a blindness camp in Omaruru District hospital in Namibia. He lost his sight to 50 years of farm labour in the Namibian sun and dust, which destroyed both of his corneas. This kind of blindness is the result of living in remote locations with prolonged exposure to fierce elements and no eye care anywhere nearby. A lack of education as to what was happening to his eyes also allowed this to occur. These camps are held all over Namibia and cater to sections of the population that do not receive regular eye care, mostly as a result of poverty. The applicant are screened and if the diagnosis is a mature cataract, they are selected as candidates for a simple operation which in fifteen minutes lends signicant sight to their world. The cataract is removed by a surgical vacuum and a new lens in inserted. Bandages are removed the next day and in most cases a real improvement in vision is the result. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Reportage for National Geographic Magazine.)

WEST BENGAL, INDIA 21 OCTOBER 2013: Blind girls Sonia, 12, and Anita Singh, 5, accompany their parents during a rainstorm while they work in the fields of their rural Indian village. Both sisters are born into poverty with congenital cataract blindness. They must accompany their parents everywhere as they cannot be left alone without risk. The surgery to cure this is simple and takes 15 minutes but because of the level of poverty in this family they have been unable to pursue the necessary operation. India has more than 12 million blind, the majority of which suffer from cataract blindness. Poverty is the main reason these millions of people are trapped in this condition. Donor funding has recently enabled both sisters to finally go for this operation. This essay is an attempt to tell the story of their lives before surgery, during the operation to regain their sight and after as they begin to discover light.

SUNDARBANS, WEST BENGAL, INDIA, 8 JANUARY 2016: Nasma Molla, 14 is currently blind with cataracts that can be cured in a fiften minute operation. Both Nasma and her brother Amyr come from a family where 4 of five people are blind. Three have been operated on so far and all recovered sight in at least one eye. Amyr is becoming progressively worse and Nasma, who is completely blind. Nasma fears being assaulted and not being able to identify her assailaint. She has taught herself to cook, despite the dangers of the fire and her meals feed her family. Nasma's mother is blind too and fears for her daughters future, stating that marrying her off is going to be very difficult if she is blind. (Photo by Brent Stirton/ Reportage for National Geographic Magazine.)

A boat of blind men are rowed to a clinic for blindness in the Sundarban islands.

WEST BENGAL, INDIA, 15 SEPTEMBER 2014: Bharat Mallik, 7, is a boy who suffers from Cataract blindness and comes from a severely impoverished Bengali family in India. Bharat’s father is a drunk and his labourer mother struggles to make ends meet. As a result he has not been treated for his cataracts. A teacher network at school notified a local social worker and as a result of his efforts Bharat is scheduled for surgery as an Ashram hospital a few hours away. Most of these villagers are so poor that transport to a hospital is not possible. As a result many children go permanently blind when like Bharat, a simple operation can restore their sight. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Reportage by Getty Images.)

WEST BENGAL, INDIA, 15 SEPTEMBER 2014: Bharat Mallik, 7, is a boy who suffers from Cataract blindness and comes from a severely impoverished Bengali family in India. Bharat’s father is a drunk and his labourer mother struggles to make ends meet. As a result he has not been treated for his cataracts. A teacher network at school notified a local social worker and as a result of his efforts Bharat is scheduled for surgery as an Ashram hospital a few hours away. Most of these villagers are so poor that transport to a hospital is not possible. As a result many children go permanently blind when like Bharat, a simple operation can restore their sight. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Reportage by Getty Images.)

WEST BENGAL, INDIA, 17 SEPTEMBER 2014: Bharat Mallik, 7, is a boy who suffers from Cataract blindness and comes from a severely impoverished Bengali family in India. He is seen at Vivekananda Mission Hospital, an eye hospital which specializes in treating the poor for little or no money. Bharat’s father is a drunk and his labourer mother struggles to make ends meet. As a result he has not been treated for his cataracts. A teacher network at school notified a local social worker and as a result of his efforts Bharat is scheduled for surgery at Vivekananda Ashram hospital a few hours away. Most of these villagers are so poor that transport to a hospital is not possible. As a result many children go permanently blind when like Bharat, a simple operation can restore their sight. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Reportage by Getty Images.)

WEST BENGAL, INDIA, 17 SEPTEMBER 2014: Bharat Mallik, 7, is a boy who suffers from Cataract blindness and comes from a severely impoverished Bengali family in India. He is seen at Vivekananda Mission Hospital, an eye hospital which specializes in treating the poor for little or no money. Bharat’s father is a drunk and his labourer mother struggles to make ends meet. As a result he has not been treated for his cataracts. A teacher network at school notified a local social worker and as a result of his efforts Bharat is scheduled for surgery at Vivekananda Ashram hospital a few hours away. Most of these villagers are so poor that transport to a hospital is not possible. As a result many children go permanently blind when like Bharat, a simple operation can restore their sight. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Reportage by Getty Images.)

PATNA, INDIA, 10 SEPTEMBER 2014: Blind Indian boy Dablu Kuma, 8, and his mother, sister and grandmother at home in a remote village in Bihar, India. Dablu has been diagnosed with Cataracts and is being sent to hospital for surgery. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Reportage by Getty Images.)

PATNA, INDIA, 10 SEPTEMBER 2014: Blind Indian boy Dablu Kuma, 8, and his mother, sister and grandmother at home in a remote village in Bihar, India. Dablu has been diagnosed with Cataracts and is being sent to hospital for surgery. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Reportage by Getty Images.)

KOLKATA, INDIA, 14 JANUARY 2016: A blind man begs on board a river ferry, he says this is the only kind of job he can get. India has the highest percentage of blind people in the world, about one percent of their population. Most of global blindness can be prevented or cured. It simply requires access to eye care and early prevention. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Reportage for National Geographic Magazine.)

SUNDARBANS, WEST BENGAL, INDIA, 8 JANUARY 2016: Nasma Molla, 14 is currently blind with cataracts that can be cured in a fiften minute operation. Both Nasma and her brother Amyr come from a family where 4 of five people are blind. Three have been operated on so far and all recovered sight in at least one eye. Amyr is becoming progressively worse and Nasma, who is completely blind. Nasma fears being assaulted and not being able to identify her assailaint. She has taught herself to cook, despite the dangers of the fire and her meals feed her family. Nasma's mother is blind too and fears for her daughters future, stating that marrying her off is going to be very difficult if she is blind. (Photo by Brent Stirton/ Reportage for National Geographic Magazine.)

SUNDARBANS, WEST BENGAL, INDIA, 8 JANUARY 2016: Nasma Molla, 14 is currently blind with cataracts that can be cured in a fiften minute operation. Both Nasma and her brother Amyr come from a family where 4 of five people are blind. Three have been operated on so far and all recovered sight in at least one eye. Amyr is becoming progressively worse and Nasma, who is completely blind. Nasma fears being assaulted and not being able to identify her assailaint. She has taught herself to cook, despite the dangers of the fire and her meals feed her family. Nasma's mother is blind too and fears for her daughters future, stating that marrying her off is going to be very difficult if she is blind. (Photo by Brent Stirton/ Reportage for National Geographic Magazine.)

YURIMAGUAS, PERU: Nacor, 5, and his brother Cadiel, 11, both suffer from generic cataracts. They live in a small rural town where their father drives a motorbike taxi and there is little money for eye surgery. Cadiel has already had some surgery at a free eye camp for the poor. Unfortunately, his one eye had to be removed and doctors have told his mother that his other eye is threatened by a complex cataract which is still too immature to operate on. Their mother Carmen also has two cataracts but has made her children her priority. She also has another older son with cataracts. Recently a local Peruvian eye doctor identified Nacor as a good candidate for cataract surgery at a free eye camp being held by SEE International. Carmen brought both her boys with her to the camp in the regional capital Tarapoto. Unfortunately Cadiel was told he still needs to wait for surgery on his remaining eye. Nacor was accepted for surgery and despite complications during the actual surgery, it seems he will make a good recovery and should see well. It is fortunate that he was identified at a young age when it is much more likely that his eyes and brain can still form a good connection. If left too long, only limited sight recovery is possible. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Verbatim Agency.)

Jose Rosas Vallalobos, 56, started losing his sight after a car accident, a trauma for which he was never treated. He also developed cataracts in both eyes that have caused him to lose further vision until he was completely blind. Jose has a large family that depend on him for their survival. He bought a home for which he paid off half and then intended to work off the other half in his small coffee plantation. His complete blindness has prevented him from doing so and his children and his wife now work the plantation in an effort to stave off their creditors. Jose feels a deep shame about this, he regrets he is not able to contribute to his family and feels he is a burden. His wife also has to guide him everywhere and in all things, he feels terrible about this. Two of Jose’s children, Wilder, 19, and Maria, 21, are also legally blind. Both have detached retinas and cataracts. A Peruvian doctor visited this family in their home town while canvassing for a blindness camp, she told the family that they should come to Tarapoto, a town three hours away for a SEE International eye camp where they can receive free surgery for their cataracts. Jose and his family came to the camp. Unfortunately, both the children were not eligible for surgery as their eyes were diagnosed as beyond help. If they had come to surgery sooner, it is possible they could have been helped. This is typical of people in rural areas with no access to eye care and illustrates to importance of immediate action if at all possible. Jose was diagnosed as having a very slim chance for any sight recovery after surgery, due to the advanced age of his cataracts and subsequent potential nerve damage. His sister was told that she had the best chance but that it would not be more than ten percent of sight, enough to be independent at least. After a difficult surgery on Jose, Dr Preeti Shah, a SEE doctor from India, was able to install a new lens in one eye and Jose’s recovery has been far better than expect

Jose Rosas Vallalobos, 56, started losing his sight after a car accident, a trauma for which he was never treated. He also developed cataracts in both eyes that have caused him to lose further vision until he was completely blind. Jose has a large family that depend on him for their survival. He bought a home for which he paid off half and then intended to work off the other half in his small coffee plantation. His complete blindness has prevented him from doing so and his children and his wife now work the plantation in an effort to stave off their creditors. Jose feels a deep shame about this, he regrets he is not able to contribute to his family and feels he is a burden. His wife also has to guide him everywhere and in all things, he feels terrible about this. Two of Jose’s children, Wilder, 19, and Maria, 21, are also legally blind. Both have detached retinas and cataracts. A Peruvian doctor visited this family in their home town while canvassing for a blindness camp, she told the family that they should come to Tarapoto, a town three hours away for a SEE International eye camp where they can receive free surgery for their cataracts. Jose and his family came to the camp. Unfortunately, both the children were not eligible for surgery as their eyes were diagnosed as beyond help. If they had come to surgery sooner, it is possible they could have been helped. This is typical of people in rural areas with no access to eye care and illustrates to importance of immediate action if at all possible. Jose was diagnosed as having a very slim chance for any sight recovery after surgery, due to the advanced age of his cataracts and subsequent potential nerve damage. His sister was told that she had the best chance but that it would not be more than ten percent of sight, enough to be independent at least. After a difficult surgery on Jose, Dr Preeti Shah, a SEE doctor from India, was able to install a new lens in one eye and Jose’s recovery has been far better than expect

Jose Rosas Vallalobos, 56, started losing his sight after a car accident, a trauma for which he was never treated. He also developed cataracts in both eyes that have caused him to lose further vision until he was completely blind. Jose has a large family that depend on him for their survival. He bought a home for which he paid off half and then intended to work off the other half in his small coffee plantation. His complete blindness has prevented him from doing so and his children and his wife now work the plantation in an effort to stave off their creditors. Jose feels a deep shame about this, he regrets he is not able to contribute to his family and feels he is a burden. His wife also has to guide him everywhere and in all things, he feels terrible about this. Two of Jose’s children, Wilder, 19, and Maria, 21, are also legally blind. Both have detached retinas and cataracts. A Peruvian doctor visited this family in their home town while canvassing for a blindness camp, she told the family that they should come to Tarapoto, a town three hours away for a SEE International eye camp where they can receive free surgery for their cataracts. Jose and his family came to the camp. Unfortunately, both the children were not eligible for surgery as their eyes were diagnosed as beyond help. If they had come to surgery sooner, it is possible they could have been helped. This is typical of people in rural areas with no access to eye care and illustrates to importance of immediate action if at all possible. Jose was diagnosed as having a very slim chance for any sight recovery after surgery, due to the advanced age of his cataracts and subsequent potential nerve damage. His sister was told that she had the best chance but that it would not be more than ten percent of sight, enough to be independent at least. After a difficult surgery on Jose, Dr Preeti Shah, a SEE doctor from India, was able to install a new lens in one eye and Jose’s recovery has been far better than expect

Jose Rosas Vallalobos, 56, started losing his sight after a car accident, a trauma for which he was never treated. He also developed cataracts in both eyes that have caused him to lose further vision until he was completely blind. Jose has a large family that depend on him for their survival. He bought a home for which he paid off half and then intended to work off the other half in his small coffee plantation. His complete blindness has prevented him from doing so and his children and his wife now work the plantation in an effort to stave off their creditors. Jose feels a deep shame about this, he regrets he is not able to contribute to his family and feels he is a burden. His wife also has to guide him everywhere and in all things, he feels terrible about this. Two of Jose’s children, Wilder, 19, and Maria, 21, are also legally blind. Both have detached retinas and cataracts. A Peruvian doctor visited this family in their home town while canvassing for a blindness camp, she told the family that they should come to Tarapoto, a town three hours away for a SEE International eye camp where they can receive free surgery for their cataracts. Jose and his family came to the camp. Unfortunately, both the children were not eligible for surgery as their eyes were diagnosed as beyond help. If they had come to surgery sooner, it is possible they could have been helped. This is typical of people in rural areas with no access to eye care and illustrates to importance of immediate action if at all possible. Jose was diagnosed as having a very slim chance for any sight recovery after surgery, due to the advanced age of his cataracts and subsequent potential nerve damage. His sister was told that she had the best chance but that it would not be more than ten percent of sight, enough to be independent at least. After a difficult surgery on Jose, Dr Preeti Shah, a SEE doctor from India, was able to install a new lens in one eye and Jose’s recovery has been far better than expect

LAKE TURKANA, NORTHERN KENYA, MAY 2010: A mentally handicapped and blind Dasenetch man, Michael, 20, in Lake Turkana North Kenya, 20 May 2010. A lack of access to proper medical care resulted in brain damage when Michael was born. His mother says he was sighted until he was 12 but lost the ability to see. This has made him a burden in his community and totally reliant on others. It remains an important priority for pastoralist tribes all over Kenya to have access to medical care in their communities in order to secure the well being of their people. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Reportage by Getty Images.)

JOHANNESBURG, SOUTH AFRICA, JUNE 2009: A blind Zimbabwean refugee photographed in slum dwellings in inner city Johannesburg, South Africa. Most of the blind are in South Africa illegally and lack official papers and ID documents which might help them to apply for limited charity. This man was part of a group of over 20 blind people who made the journey with the help of two sighted people. They say they fled a complete lack of economic opportunity in Zimbabwe's failed state and had no choice but to come to South Africa to survive. They could no longer beg for their survival in Zimbabwe as people simply no longer have anything to give. As a result many of these blind people have made long journeys with their guides, families or by relying on the kindness of strangers. They crossed the Limpopo River to avoid the border authorities and lived in the bush for many weeks before being able to organise a ride by train or bus down to Johannesburg. All of this they did for the opportunity to beg in a more affluent economy. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Reportage by Getty Images.)

JOHANNESBURG, SOUTH AFRICA, JUNE 2009: Blind Zimbabwean refugees photographed in slum dwellings in inner city Johannesburg, South Africa, 17 June 2009. Most of the blind are in South Africa illegally and lack official papers and ID documents which might help them to apply for limited charity. They say they fled a complete lack of economic opportunity in Zimbabwe's failed state and had no choice but to come to South Africa to survive. They could no longer beg for their survival in Zimbabwe as people simply no longer have anything to give. As a result many of these blind people have made long journeys with their guides, families or by relying on the kindness of strangers. They crossed the Limpopo River to avoid the border authorities and lived in the bush for many weeks before being able to organise a ride by train or bus down to Johannesburg. All of this they did for the opportunity to beg in a more affluent economy. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Reportage by Getty Images.)

JOHANNESBURG, SOUTH AFRICA, JUNE 2009: Blind Zimbabwean refugees photographed in slum dwellings in inner city Johannesburg, South Africa, 17 June 2009. Most of the blind are in South Africa illegally and lack official papers and ID documents which might help them to apply for limited charity. They say they fled a complete lack of economic opportunity in Zimbabwe's failed state and had no choice but to come to South Africa to survive. They could no longer beg for their survival in Zimbabwe as people simply no longer have anything to give. As a result many of these blind people have made long journeys with their guides, families or by relying on the kindness of strangers. They crossed the Limpopo River to avoid the border authorities and lived in the bush for many weeks before being able to organise a ride by train or bus down to Johannesburg. All of this they did for the opportunity to beg in a more affluent economy. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Reportage by Getty Images.)

OHANGWENA DISTRICT, NORTHERN NAMIBIA, 8TH NOVEMBER 2015: Frans Shilongo, 77, waits at the gate to his family compound for his nephew to come home. Frans is blind and entirely dependent on his family for his daily needs. For millions of people around the world blindness is something that affects entire families and communities. In the majority world children are often the caregivers of the blind. This can inhibit their education, their movement, their social circle and more. The majority of this is caused by blindness affecting the elderly; Glaucoma is common in many cases as is Corneal scarring and other issues affecting sight. Children most often function as a walking guide for these blinded people, helping them to get water, to bathe, to walk around and to fetch what is needed. Blindness in most instances is treatable if the issue is caught early enough. Access to quality eye care and education on the dangers are often lacking, hence the large incidence of blindness in the more remote regions of the world. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Reportage for National Geographic Magazine.)

OHANGWENA DISTRICT, NORTHERN NAMIBIA, 8TH NOVEMBER 2015: Jason Hangula, 45, lost his sight in 2007 to a glucoma condition which was left untreated for too long. Damage to the optic nerve means that he is dependent on the children in his family compound for daily guidance to get around. He is seen with his niece Claudia Haindongo, 11, who has been assisting him ever since he lost his sight. For millions of people around the world blindness is something that affects entire families and communities. In the majority world children are often the caregivers of the blind. This can inhibit their education, their movement, their social circle and more. The majority of this is caused by blindness affecting the elderly; Glaucoma is common in many cases as is Corneal scarring and other issues affecting sight. Children most often function as a walking guide for these blinded people, helping them to get water, to bathe, to walk around and to fetch what is needed. Blindness in most instances is treatable if the issue is caught early enough. Access to quality eye care and education on the dangers are often lacking, hence the large incidence of blindness in the more remote regions of the world. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Reportage for National Geographic Magazine.)

OHANGWENA DISTRICT, NORTHERN NAMIBIA, 8TH NOVEMBER 2015: Lusina Nghitotelwa helps to guide her blind grandmother Lucia on her way to the bathroom close to the family compound in Ohangwena, Namiba. For millions of people around the world blindness is something that affects entire families and communities. In the majority world children are often the caregivers of the blind. This can inhibit their education, their movement, their social circle and more. The majority of this is caused by blindness affecting the elderly; Glaucoma is common in many cases as is Corneal scarring and other issues affecting sight. Children most often function as a walking guide for these blinded people, helping them to get water, to bathe, to walk around and to fetch what is needed. Blindness in most instances is treatable if the issue is caught early enough. Access to quality eye care and education on the dangers are often lacking, hence the large incidence of blindness in the more remote regions of the world. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Reportage for National Geographic Magazine.)

OHANGWENA DISTRICT, NORTHERN NAMIBIA, 8TH NOVEMBER 2015: Lovisa Shangadi, 72, is guided by her grandchild Lavina Shangadi, 7, on her way to the bathroom. For millions of people around the world blindness is something that affects entire families and communities. In the majority world children are often the caregivers of the blind. This can inhibit their education, their movement, their social circle and more. The majority of this is caused by blindness affecting the elderly; Glaucoma is common in many cases as is Corneal scarring and other issues affecting sight. Children most often function as a walking guide for these blinded people, helping them to get water, to bathe, to walk around and to fetch what is needed. Blindness in most instances is treatable if the issue is caught early enough. Access to quality eye care and education on the dangers are often lacking, hence the large incidence of blindness in the more remote regions of the world. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Reportage for National Geographic Magazine.)

OHANGWENA DISTRICT, NORTHERN NAMIBIA, 8TH NOVEMBER 2015: Esther Shangadi, 79, suffers from end stage Glaucoma, ensuring her blindness. She is guided around her compound by five year old Gabriel Paulus, her constant companion and everyday sight guide. For millions of people around the world blindness is something that affects entire families and communities. In the majority world children are often the caregivers of the blind. This can inhibit their education, their movement, their social circle and more. The majority of this is caused by blindness affecting the elderly; Glaucoma is common in many cases as is Corneal scarring and other issues affecting sight. Children most often function as a walking guide for these blinded people, helping them to get water, to bathe, to walk around and to fetch what is needed. Blindness in most instances is treatable if the issue is caught early enough. Access to quality eye care and education on the dangers are often lacking, hence the large incidence of blindness in the more remote regions of the world. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Reportage for National Geographic Magazine.)

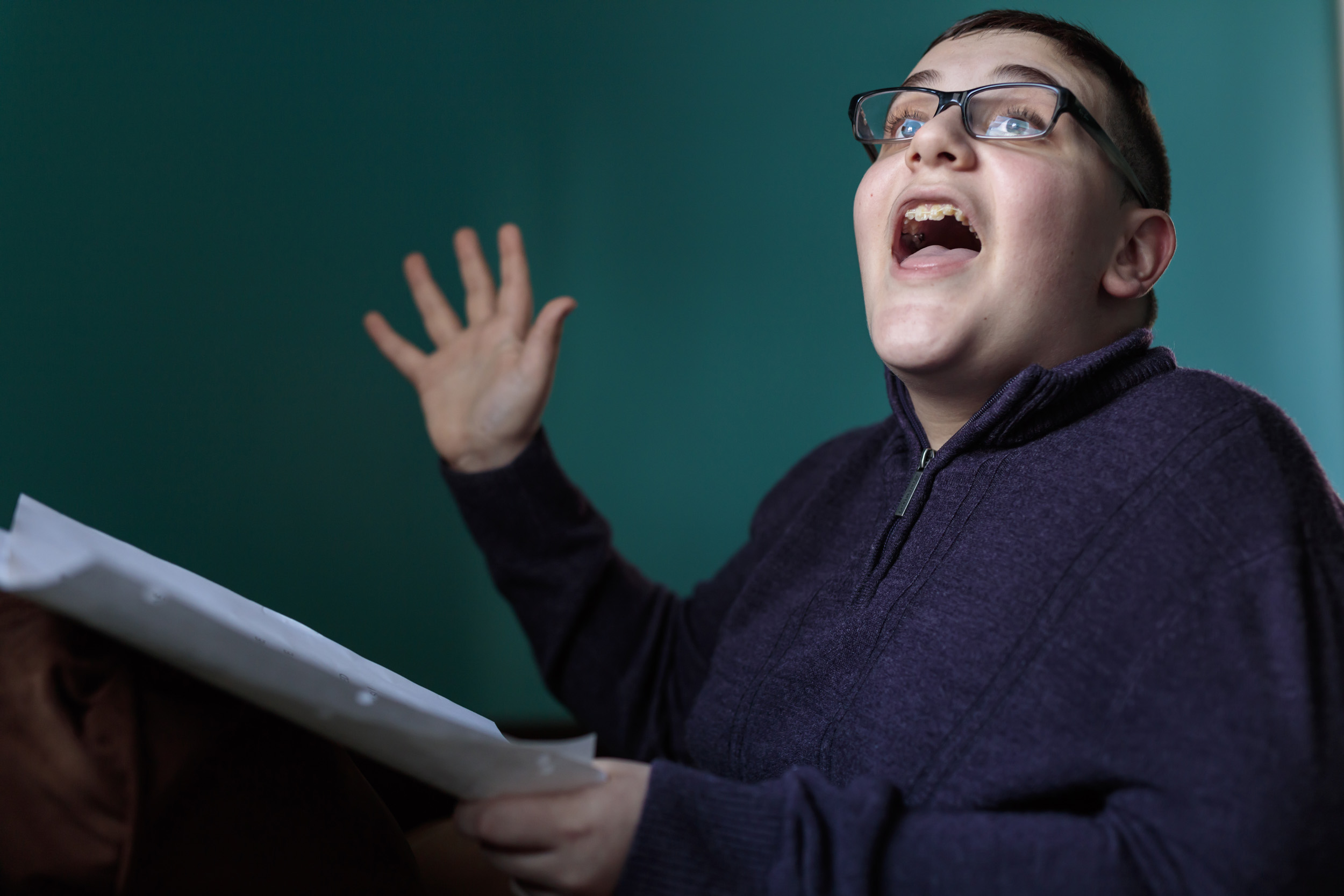

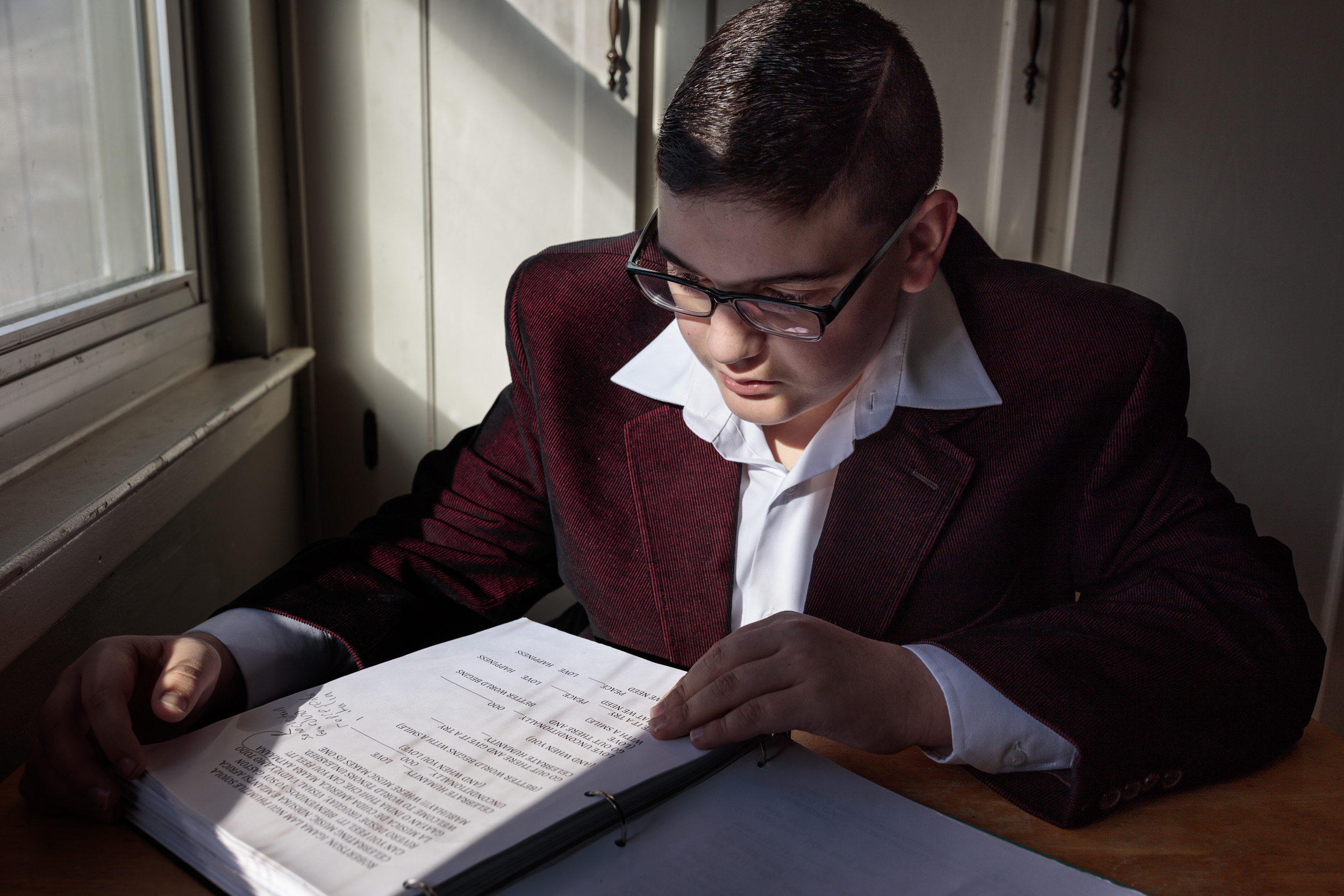

VIVEKANANDA MISSION ASRAM, HALDIA, WEST BENGAL, INDIA, JANUARY 14, 2016: A young boy with severely impaired vision seen in the hostel residence of the Vivekananda Mission Asram school for the blind. This is the highest rated school for blind children in India, the country with the highest number of blind people, arond 1% of their population, approximately 12 million people. Vivekanda Mission Asram provides care to some of the poorest of blind children, providing them with an education and tools for life survival once they leave the Asram after graduating. The children learn a normal school curiculum through braile and a team of dedicated teachers. Vocationa training is also available at the Asram in weaving, candle making amongst other skills that can add meaning to a blind life in India. Most of the blind in India end up as beggars, this school offers students a chance to be more than that. A number of their students have gone on to become senior teachers for sighted pupils, lawyers and business people. In these images the boys and girls are seen attending school lessons, learning Braille, music as well as scenes from their hostel residence and sports activities. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Reportage for National Geographic Magazine.)

VIVEKANANDA MISSION ASRAM, HALDIA, WEST BENGAL, INDIA, JANUARY 14, 2016: Scenes with blind boys in the hostel residence of the Vivekananda Mission Asram school for the blind. This is the highest rated school for blind children in India, the country with the highest number of blind people, arond 1% of their population, approximately 12 million people. Vivekanda Mission Asram provides care to some of the poorest of blind children, providing them with an education and tools for life survival once they leave the Asram after graduating. The children learn a normal school curiculum through braile and a team of dedicated teachers. Vocationa training is also available at the Asram in weaving, candle making amongst other skills that can add meaning to a blind life in India. Most of the blind in India end up as beggars, this school offers students a chance to be more than that. A number of their students have gone on to become senior teachers for sighted pupils, lawyers and business people. In these images the boys and girls are seen attending school lessons, learning Braille, music as well as scenes from their hostel residence and sports activities. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Reportage for National Geographic Magazine.)

VIVEKANANDA MISSION ASRAM, HALDIA, WEST BENGAL, INDIA, JANUARY 14, 2016: Scenes with blind boys in the hostel residence of the Vivekananda Mission Asram school for the blind. This is the highest rated school for blind children in India, the country with the highest number of blind people, arond 1% of their population, approximately 12 million people. Vivekanda Mission Asram provides care to some of the poorest of blind children, providing them with an education and tools for life survival once they leave the Asram after graduating. The children learn a normal school curiculum through braile and a team of dedicated teachers. Vocationa training is also available at the Asram in weaving, candle making amongst other skills that can add meaning to a blind life in India. Most of the blind in India end up as beggars, this school offers students a chance to be more than that. A number of their students have gone on to become senior teachers for sighted pupils, lawyers and business people. In these images the boys and girls are seen attending school lessons, learning Braille, music as well as scenes from their hostel residence and sports activities. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Reportage for National Geographic Magazine.)

VIVEKANANDA MISSION ASRAM, HALDIA, WEST BENGAL, INDIA, JANUARY 14, 2016: Raghunandan Maity, 19, studies braille at the Vivekananda Mission Asram school for the blind. He has been at the school since he was 4 years old and credits his future to the school and the skills he has learnt there. This is the highest rated school for blind children in India, the country with the highest number of blind people, arond 1% of their population, approximately 12 million people. Vivekanda Mission Asram provides care to some of the poorest of blind children, providing them with an education and tools for life survival once they leave the Asram after graduating. The children learn a normal school curiculum through braile and a team of dedicated teachers. Vocationa training is also available at the Asram in weaving, candle making amongst other skills that can add meaning to a blind life in India. Most of the blind in India end up as beggars, this school offers students a chance to be more than that. A number of their students have gone on to become senior teachers for sighted pupils, lawyers and business people. In these images the boys and girls are seen attending school lessons, learning Braille, music as well as scenes from their hostel residence and sports activities. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Reportage for National Geographic Magazine.)

VIVEKANANDA MISSION ASRAM, HALDIA, WEST BENGAL, INDIA, JANUARY 17, 2016: Blind school kids from the Vivekananda Mission Asram school for the blind learn the solar system from a model in a classroom with the headmaster Mr Panda. Models are invaluable in educating the blind, enabling them to have a three dimensional sense of what the world around them looks like. This is the highest rated school for blind children in India, the country with the highest number of blind people, arond 1% of their population, approximately 12 million people. Vivekanda Mission Asram provides care to some of the poorest of blind children, providing them with an education and tools for life survival once they leave the Asram after graduating. The children learn a normal school curiculum through braile and a team of dedicated teachers. Vocationa training is also available at the Asram in weaving, candle making amongst other skills that can add meaning to a blind life in India. Most of the blind in India end up as beggars, this school offers students a chance to be more than that. A number of their students have gone on to become senior teachers for sighted pupils, lawyers and business people. In these images the boys and girls are seen attending school lessons, learning Braille, music as well as scenes from their hostel residence and sports activities. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Reportage for National Geographic Magazine.)

VIVEKANANDA MISSION ASRAM, HALDIA, WEST BENGAL, INDIA, JANUARY 14, 2016: A blind student shaves in dappled light in the bathroom in the hostel residence of the Vivekananda Mission Asram school for the blind. This is the highest rated school for blind children in India, the country with the highest number of blind people, arond 1% of their population, approximately 12 million people. Vivekanda Mission Asram provides care to some of the poorest of blind children, providing them with an education and tools for life survival once they leave the Asram after graduating. The children learn a normal school curiculum through braile and a team of dedicated teachers. Vocationa training is also available at the Asram in weaving, candle making amongst other skills that can add meaning to a blind life in India. Most of the blind in India end up as beggars, this school offers students a chance to be more than that. A number of their students have gone on to become senior teachers for sighted pupils, lawyers and business people. In these images the boys and girls are seen attending school lessons, learning Braille, music as well as scenes from their hostel residence and sports activities. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Reportage for National Geographic Magazine.)

VIVEKANANDA MISSION ASRAM, HALDIA, WEST BENGAL, INDIA, JANUARY 14, 2016: Blind boys talk amongst themselves inside their dorm room in the hostel residence of the Vivekananda Mission Asram school for the blind. This is the highest rated school for blind children in India, the country with the highest number of blind people, arond 1% of their population, approximately 12 million people. Vivekanda Mission Asram provides care to some of the poorest of blind children, providing them with an education and tools for life survival once they leave the Asram after graduating. The children learn a normal school curiculum through braile and a team of dedicated teachers. Vocationa training is also available at the Asram in weaving, candle making amongst other skills that can add meaning to a blind life in India. Most of the blind in India end up as beggars, this school offers students a chance to be more than that. A number of their students have gone on to become senior teachers for sighted pupils, lawyers and business people. In these images the boys and girls are seen attending school lessons, learning Braille, music as well as scenes from their hostel residence and sports activities. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Reportage for National Geographic Magazine.)

VIVEKANANDA MISSION ASRAM, HALDIA, WEST BENGAL, INDIA, JANUARY 14, 2016: Blind boys play chess in their dorm room in the hostel residence of the Vivekananda Mission Asram school for the blind. The game requires extraordinary memory skills for a blind person and the spectators are also likely to feel the pieces to know how the game is progressing. It is a good example of how certain skill sets are highly developed in a blind person in the absence of sight. Vivekananda is the highest rated school for blind children in India, the country with the highest number of blind people, arond 1% of their population, approximately 12 million people. Vivekanda Mission Asram provides care to some of the poorest of blind children, providing them with an education and tools for life survival once they leave the Asram after graduating. The children learn a normal school curiculum through braile and a team of dedicated teachers. Vocationa training is also available at the Asram in weaving, candle making amongst other skills that can add meaning to a blind life in India. Most of the blind in India end up as beggars, this school offers students a chance to be more than that. A number of their students have gone on to become senior teachers for sighted pupils, lawyers and business people. In these images the boys and girls are seen attending school lessons, learning Braille, music as well as scenes from their hostel residence and sports activities. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Reportage for National Geographic Magazine.)

VIVEKANANDA MISSION ASRAM, HALDIA, WEST BENGAL, INDIA, JANUARY 17, 2016: Blind children make their way from the hostel residence of the Vivekananda Mission Asram school for the blind across a busy street on their way to school. This is the highest rated school for blind children in India, the country with the highest number of blind people, arond 1% of their population, approximately 12 million people. Vivekanda Mission Asram provides care to some of the poorest of blind children, providing them with an education and tools for life survival once they leave the Asram after graduating. The children learn a normal school curiculum through braile and a team of dedicated teachers. Vocationa training is also available at the Asram in weaving, candle making amongst other skills that can add meaning to a blind life in India. Most of the blind in India end up as beggars, this school offers students a chance to be more than that. A number of their students have gone on to become senior teachers for sighted pupils, lawyers and business people. In these images the boys and girls are seen attending school lessons, learning Braille, music as well as scenes from their hostel residence and sports activities. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Reportage for National Geographic Magazine.)

VIVEKANANDA MISSION ASRAM, WEST BENGAL, INDIA, 14 JANUARY 2016: Annya Polley, 15, has been a pupil at the Vivekananda Mission Asram School for the blind for two year. She lives at the school residence and says that she attends Vivekananda because her previous school could not cater for her blindness and she was neglected. This is often the case for children around the world who live with severely impaired vision. Vivekananda is regarded as one the best schools of its kind in India but there is shortage of these facilities in a country with the largest numbers of blind people. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Reportage for National Geographic Magazine.)

VIVEKANANDA MISSION ASRAM, HALDIA, WEST BENGAL, INDIA, JANUARY 16, 2016: Blind male students of the Vivekananda Mission Asram school for the blind are seen at their calisthenics and yoga class in the main assembly hall. Vivekananda has had a number of paraolympic athletes. This is the highest rated school for blind children in India, the country with the highest number of blind people, arond 1% of their population, approximately 12 million people. Vivekanda Mission Asram provides care to some of the poorest of blind children, providing them with an education and tools for life survival once they leave the Asram after graduating. The children learn a normal school curiculum through braile and a team of dedicated teachers. Vocationa training is also available at the Asram in weaving, candle making amongst other skills that can add meaning to a blind life in India. Most of the blind in India end up as beggars, this school offers students a chance to be more than that. A number of their students have gone on to become senior teachers for sighted pupils, lawyers and business people. In these images the boys and girls are seen attending school lessons, learning Braille, music as well as scenes from their hostel residence and sports activities. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Reportage for National Geographic Magazine.)

VIVEKANANDA MISSION ASRAM, HALDIA, WEST BENGAL, INDIA, JANUARY 14, 2016: Scenes with blind boys in the hostel residence of the Vivekananda Mission Asram school for the blind. This is the highest rated school for blind children in India, the country with the highest number of blind people, arond 1% of their population, approximately 12 million people. Vivekanda Mission Asram provides care to some of the poorest of blind children, providing them with an education and tools for life survival once they leave the Asram after graduating. The children learn a normal school curiculum through braile and a team of dedicated teachers. Vocationa training is also available at the Asram in weaving, candle making amongst other skills that can add meaning to a blind life in India. Most of the blind in India end up as beggars, this school offers students a chance to be more than that. A number of their students have gone on to become senior teachers for sighted pupils, lawyers and business people. In these images the boys and girls are seen attending school lessons, learning Braille, music as well as scenes from their hostel residence and sports activities. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Reportage for National Geographic Magazine.)

VIVEKANANDA MISSION ASRAM, HALDIA, WEST BENGAL, INDIA, JANUARY 14, 2016: Scenes with blind boys in the hostel residence of the Vivekananda Mission Asram school for the blind. This is the highest rated school for blind children in India, the country with the highest number of blind people, arond 1% of their population, approximately 12 million people. Vivekanda Mission Asram provides care to some of the poorest of blind children, providing them with an education and tools for life survival once they leave the Asram after graduating. The children learn a normal school curiculum through braile and a team of dedicated teachers. Vocationa training is also available at the Asram in weaving, candle making amongst other skills that can add meaning to a blind life in India. Most of the blind in India end up as beggars, this school offers students a chance to be more than that. A number of their students have gone on to become senior teachers for sighted pupils, lawyers and business people. In these images the boys and girls are seen attending school lessons, learning Braille, music as well as scenes from their hostel residence and sports activities. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Reportage for National Geographic Magazine.)

VIVEKANANDA MISSION ASRAM, WEST BENGAL, INDIA, 14 JANUARY 2016: Jhulan Mukherjee, 39, is a former pupil from the Vivekananda Mission Asram School for the blind, she is a successful teacher at a school for sighted pupils today. Jhulan learnt braille at home from a young age but says she would not have had any success without her time at Vivekananda. Jhulan had a very difficult time with prejudice against the blind, despite being a very talented student. After school she studied English Literature for 3 years attaining her Bachelors degree, she then did a masters in English as well as another BA in education. She decided to become a teacher but was refused access to the entrance examinations. She became part of a movement for the rights of the Blind in India and took her case to court. The court ruled that she had the right to become a teacher and Jhulan passed her examinations on her first try. The first school she was assigned to was prejudiced against her and refused to let her teach. Another legal fight ensued and the District Inspector of Schools intervened on Jhulan's behalf and actually declassified the school for their prejudicial audacity. Jhulan then had to deal with the School Service Commision regarding her blindness but passed her exam and was finally allowed to teach at her second school posting. Jhulan has taught successfully as a blind person at Talbagicha High School in Kharagpur, West Bengal for more than ten years now. She is seen with her son who has the same hereditary issues as herself. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Reportage for National Geographic Magazine.)

A schoolgirl with Ocular Albinism. Ireland

Exercise class for the blind, Ireland

Animal therapy for the blind, Ireland

Animal therapy for the blind, Ireland

Blind boxer prepares for a fight, Dublin, Ireland.

SUNDARBANS, INDIA: A blind woman with a child feels her way on to a boat that is a mobile camp for eye care in a remote part of the Sundarban islands in India. These boats offer general eye health diagnosis to extremely impoverished villages deep within the Sundarbans. Dr Asim Sil’s extremely dedicated team uses these boats to get around the Sundarbans and often works from early morning to late at night on patients who would otherwise have no access to good eye care. The goal of the team is to educate and offer refractive services, ie glasses; to diagnose eye health problems and to offer surgical solutions to patients who need them, including transport to the hospitals. These services are provided free of charge. Dr Sil has worked on eye care in the Sundarbans since 1989, and along with his team has been of service to thousands of patients in this remote region of India. A high povery index and remoteness of location coupled with a lack of access to quality eye care has seen India become the country with the highest number of blind people. Most of these cases began as problems that if diagnosed earlier, could have been prevented.

Sundarbans, India, 11 January 2016: Dr Asim Sil leads a team of eye care specialists on a boat-camp for eye care in a remote part of the Sundarbans, India. These boats are often used in partnership with other NGO’s, offering general healthcare facilities as well as eye health diagnosis to extremely impoverished villages deep within the Sundarbans. Dr Sil’s team uses boats to get around the Sundarbans and often works from early morning to late at night on patients who would otherwise not have access to good eye care. The goal of the team is to educate and offer refractive services, ie glasses; to diagnose eye health problems and to offer surgical solutions to patients who need them, including transport to the hospitals. These services are provided free of charge by Vivekananda Mission Asram hospital. Dr Sil has worked on eye care in the Sundarbans since 1989, and along with his team has been of service to thousands of patients in this remote region of India. A high povery index and remoteness of location coupled with a lack of access to quality eye care has seen India become the country with the highest number of blind people. Most of these cases began as problems that if diagnosed earlier, could have been prevented. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Reportage for National Geographic Magazine.)

Sundarbans, India, 11 January 2016: Dr Asim Sil leads a team of eye care specialists on a boat-camp for eye care in a remote part of the Sundarbans, India. These boats are often used in partnership with other NGO’s, offering general healthcare facilities as well as eye health diagnosis to extremely impoverished villages deep within the Sundarbans. Dr Sil’s team uses boats to get around the Sundarbans and often works from early morning to late at night on patients who would otherwise not have access to good eye care. The goal of the team is to educate and offer refractive services, ie glasses; to diagnose eye health problems and to offer surgical solutions to patients who need them, including transport to the hospitals. These services are provided free of charge by Vivekananda Mission Asram hospital. Dr Sil has worked on eye care in the Sundarbans since 1989, and along with his team has been of service to thousands of patients in this remote region of India. A high povery index and remoteness of location coupled with a lack of access to quality eye care has seen India become the country with the highest number of blind people. Most of these cases began as problems that if diagnosed earlier, could have been prevented. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Reportage for National Geographic Magazine.)

Sundarbans, India, 11 January 2016: Dr Asim Sil leads a team of eye care specialists on a boat-camp for eye care in a remote part of the Sundarbans, India. These boats are often used in partnership with other NGO’s, offering general healthcare facilities as well as eye health diagnosis to extremely impoverished villages deep within the Sundarbans. Dr Sil’s team uses boats to get around the Sundarbans and often works from early morning to late at night on patients who would otherwise not have access to good eye care. The goal of the team is to educate and offer refractive services, ie glasses; to diagnose eye health problems and to offer surgical solutions to patients who need them, including transport to the hospitals. These services are provided free of charge by Vivekananda Mission Asram hospital. Dr Sil has worked on eye care in the Sundarbans since 1989, and along with his team has been of service to thousands of patients in this remote region of India. A high povery index and remoteness of location coupled with a lack of access to quality eye care has seen India become the country with the highest number of blind people. Most of these cases began as problems that if diagnosed earlier, could have been prevented. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Reportage for National Geographic Magazine.)

SUNDARABANS, WEST BENGAL, INDIA, 8 JANUARY 2016: Images from Goshaba Vision Center, a center where optical care is provided to remote Indian communities. These centres are now found across the more remote areas and are primarly used to cater for refractions needs, ie glasses and also to identify more serious issues which can then be referred to clinics and hospital and transport can be co-ordinated for these patients. Most of the demographic who utilizes these facilities are economically challenged and these centers fill a vital gap for those who otherwise would not be able to access eye care. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Reportage for National Geographic Magazine.)

Sundarbans, India: Two Indian gentlemen receive an eye test in a remote part of the Sundarban islands, India. These remote mobile camps offer eye health diagnosis for the first time to extremely impoverished villages deep within the Sundarban islands. Dr Asim Sil’s team uses boats to get around the Sundarbans and often works from early morning to late at night on patients who would otherwise not have access to good eye care. The goal of the team is to educate and offer refractive services, ie glasses; to diagnose eye health problems and to offer surgical solutions to patients who need them, including transport to the hospitals. These services are provided free of charge. Dr Sil has worked on eye care in the Sundarbans since 1989, and along with his team has been of service to thousands of patients in this remote region of India. A high povery index and remoteness of location coupled with a lack of access to quality eye care has seen India become the country with the highest number of blind people. Most of these cases began as problems that if diagnosed earlier, could have been prevented.

SUNDARBANS, WEST BENGAL, INDIA, 10 JANUARY 2016: Satish Goswani, a Hindu priests poses for a portrait on his way home after temple. He is wearing proctive glasses he received after recent eye surgery made possible by a local NGO working in the remote Sundarban region. Remoteness and a high poverty demographic have meant that many people in the more remote regions of the world were consigned to blindness. Access to quality eye care was just not possible but this is changing as logisitics and motivated and educated eye care NGO's have changed the face of places like the Sundarbans. Eye camps are held regularly by sattelite workers who identify issues and attempt to facilitate surgery for those in need. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Reportage for National Geographic Magazine.)

SHRI BHOJAY SARVODAYA EYE HOSPITAL, BHUJ, KUTCH, INDIA, JULY 22 2015: Eye surgeons Janak and Preeti Shah working via headlamp on a surgical operation during a powercut in this remote region of India. Dr Janak Shah is an accomplished and prolific eye surgeon who volunteers his services to the global poor via SEE International, an NGO with a focus on curing blindness. He and his wife Preeti are seen examining and performing eye surgery at the Shri Bhojay Sarvodaya Eye hospital close to the India Pakistan border. This is a new hospital that offers modern facilities to SEE where Janak can run a blindness camp as well as perform the surgeries required. Janak graduated from the University of Bombay in 1991, and completed his residency in ophthalmology in 1996. He’s been volunteering with SEE International as an eye surgeon since 1996, and in 2013, passed the milestone of 100 SEE expeditions. He is SEE’s most prolific doctor and has worked in places like the Peruvian Jungle, Gaza Strip, Lebanon, Mongolia, China, Brazil and many other remote locations. He has worked all over India and has performed thousands of eye surgeries, addressing every kind of illness. Janak is a proud adherent of the Jainism religion; he is a strong believer in their religious tenants of mankind being one. Janak often works with his wife Preeti, herself a talented eye surgeon. Together they are a formidable force and can work quickly on a multitude of surgeries in a single day. They have two daughters, one of 11 and the other 15. Both girls often travel with their parents on their volunteer trips for SEE and actively assistant in patient diagnosis as well as assisting their parents in surgery. Janak and Preeti both believe this gives the girls a real perspective on their place in the world and helps to bind them as a family unit. The Shahs live in Mumbai, India and run a successful eye surgery practice when they are not volunteering for SEE International. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Novartis)

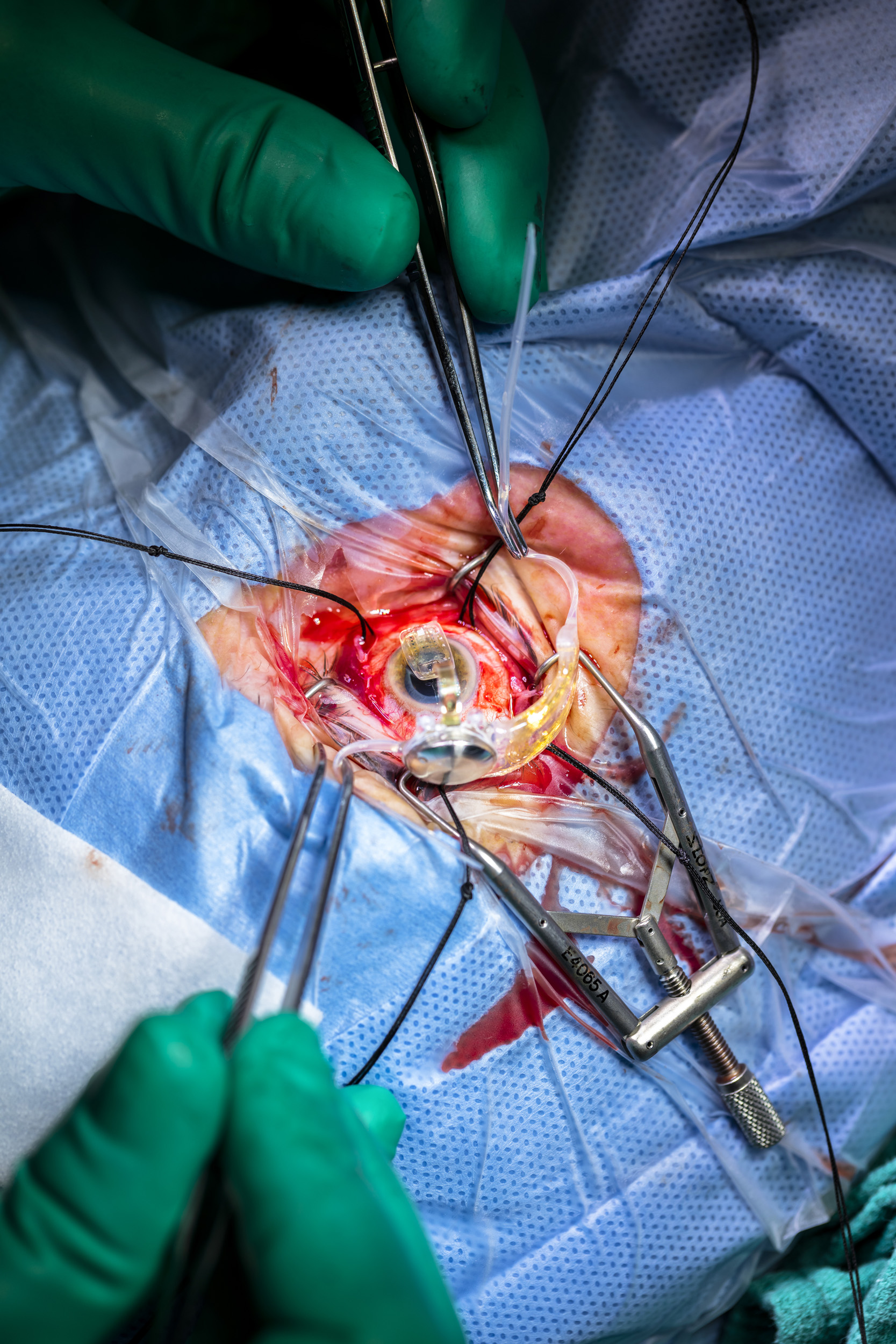

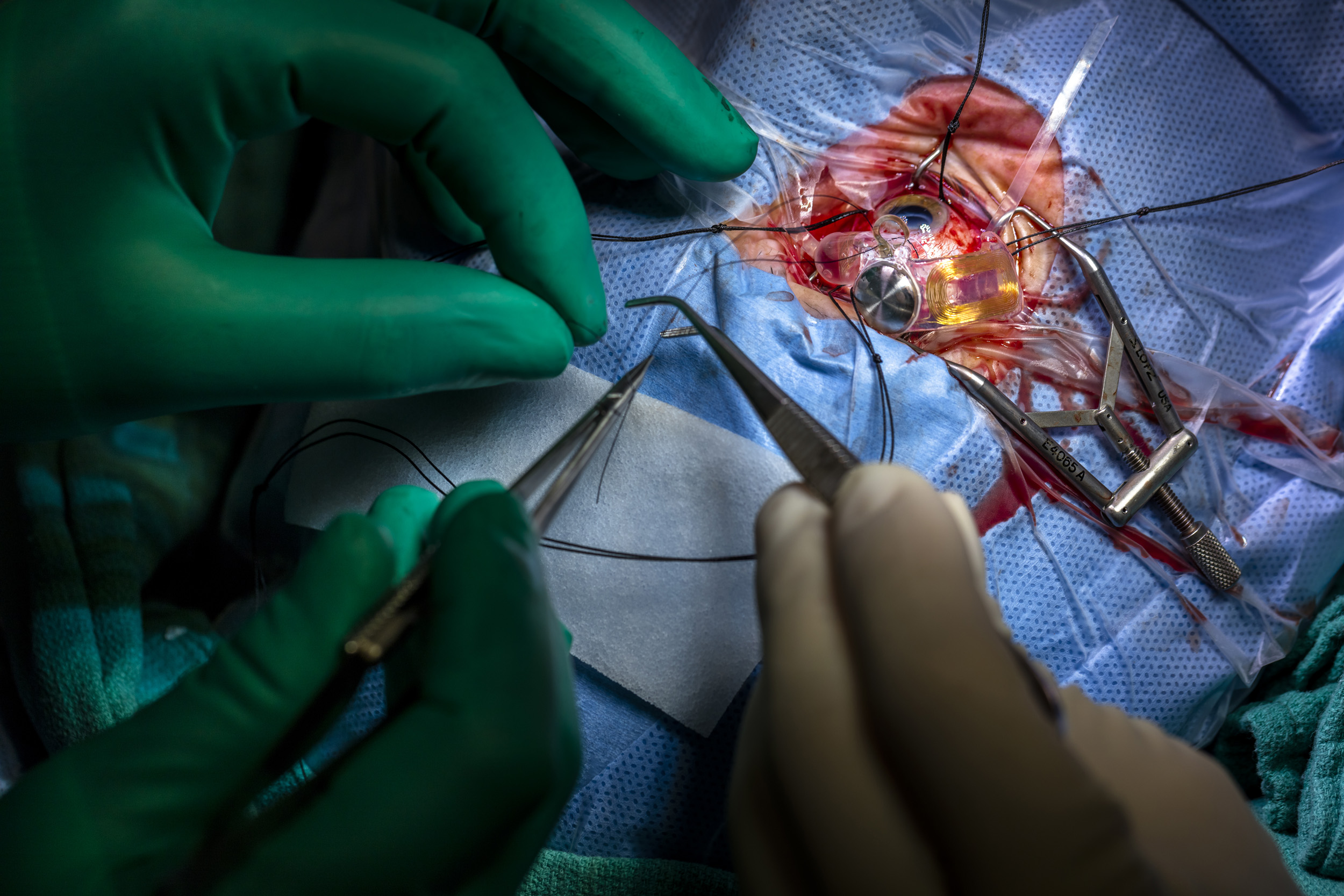

KOLKATA, INDIA, 13 JANUARY 2016: A Corneal graft is performed at the Vivekananda Mission Asram hospital on the outskirts of Kolkata. A cornea from a deceased donor is cut to precise measurements, the patients internal cataract is removed, a lens inserted and then the new Cornea sewn on to the eye. The entire procedure takes just over one hour to perform and in this case was performed free for a man who could not afford this treatment, a case representing most of the people in India in need of this kind of surgery. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Reportage for National Geographic Magazine.)

KOLKATA, INDIA, 13 JANUARY 2016: A Corneal graft is performed at the Vivekananda Mission Asram hospital on the outskirts of Kolkata. A cornea from a deceased donor is cut to precise measurements, the patients internal cataract is removed, a lens inserted and then the new Cornea sewn on to the eye. The entire procedure takes just over one hour to perform and in this case was performed free for a man who could not afford this treatment, a case representing most of the people in India in need of this kind of surgery. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Reportage for National Geographic Magazine.)

PATNA, INDIA, 10 SEPTEMBER 2014: Blind Indian patients make their way to and from a blindess camp on a remote river island where they will be diagnosed with Cataracts, Glaucoma and other eye issues and sent to hospital for surgery. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Reportage by Getty Images.)

PATNA, INDIA, 10 SEPTEMBER 2014: Blind Indian boy Dablu Kuma, 8, and his mother make their way to and from a blindess camp on a remote river island where he is diagnosed with Cataracts and sent to hospital for surgery. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Reportage by Getty Images.)

PATNA, INDIA, 10 SEPTEMBER 2014: Blind Indian boy Dablu Kuma, 8, and his mother make their way to and from a blindess camp on a remote river island where he is diagnosed with Cataracts and sent to hospital for surgery. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Reportage by Getty Images.)

PATNA, INDIA, 10 SEPTEMBER 2014: Blind Indian boy Dablu Kuma, 8, and his mother make their way to and from a blindess camp on a remote river island where he is diagnosed with Cataracts and sent to hospital for surgery. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Reportage by Getty Images.)

PATNA, INDIA, 10 SEPTEMBER 2014: Blind Indian boy Dablu Kuma, 8, and his mother make their way to and from a blindess camp on a remote river island where he is diagnosed with Cataracts and sent to hospital for surgery. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Reportage by Getty Images.)

WEST BENGAL, INDIA, 17 SEPTEMBER 2014: Bharat Mallik, 7, is a boy who suffers from Cataract blindness and comes from a severely impoverished Bengali family in India. He is seen at Vivekananda Mission Hospital, an eye hospital which specializes in treating the poor for little or no money. Bharat’s father is a drunk and his labourer mother struggles to make ends meet. As a result he has not been treated for his cataracts. A teacher network at school notified a local social worker and as a result of his efforts Bharat is scheduled for surgery at Vivekananda Ashram hospital a few hours away. Most of these villagers are so poor that transport to a hospital is not possible. As a result many children go permanently blind when like Bharat, a simple operation can restore their sight. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Reportage by Getty Images.)

AKHAND JYOTI EYE HOSPITAL, PATNA, BIHAR, INDIA, 10 SEPTEMBER 2014: Eye surgery patients recover in a mass ward at Akhand Jyoti Eye Hospital, the third largest eye hospital in India. This hospital performed over 65 000 eye surgeries last year, often averaging over 400 surgeries a day. They cater to the poorest of the poor in the poorest state in India. Over 2 thirds of their surgeries are free for the poor. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Reportage by Getty Images.)

AKHAND JYOTI EYE HOSPITAL, PATNA, BIHAR, INDIA, 10 SEPTEMBER 2014: Eye surgery patients recover in a mass ward at Akhand Jyoti Eye Hospital, the third largest eye hospital in India. This hospital performed over 65 000 eye surgeries last year, often averaging over 400 surgeries a day. They cater to the poorest of the poor in the poorest state in India. Over 2 thirds of their surgeries are free for the poor. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Reportage by Getty Images.)

AKHAND JYOTI EYE HOSPITAL, PATNA, BIHAR, INDIA, 10 SEPTEMBER 2014: Eye surgery patients recover in a mass ward at Akhand Jyoti Eye Hospital, the third largest eye hospital in India. This hospital performed over 65 000 eye surgeries last year, often averaging over 400 surgeries a day. They cater to the poorest of the poor in the poorest state in India. Over 2 thirds of their surgeries are free for the poor. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Reportage by Getty Images.)

SILIGURI, DARJEELING DISTRICT, INDIA, JULY 22 2015: Dr Janak Shah is an accomplished and prolific eye surgeon who volunteers his services to the global poor via SEE International, an NGO with a focus on curing blindness. He is seen examining and performing eye surgery at the Baba Loknath Eye Mission hospital. This is a long established religious mission that offers facilities to SEE where Janak can run a blindness camp as well as perform the surgeries required. Janak graduated from the University of Bombay in 1991, and completed his residency in ophthalmology in 1996. He’s been volunteering with SEE International as an eye surgeon since 1996, and in 2013, passed the milestone of 100 SEE expeditions. He is SEE’s most prolific doctor and has worked in places like the Peruvian Jungle, Gaza Strip, Lebanon, Mongolia, China, Brazil and many other remote locations. He has worked all over India and has performed thousands of eye surgeries, addressing every kind of illness. Janak is a proud adherent of the Jainism religion; he is a strong believer in their religious tenants of mankind being one. Janak often works with his wife Preeti, herself a talented eye surgeon. Together they are a formidable force and can work quickly on a multitude of surgeries in a single day. They have two daughters, one of 11 and the other 15. Both girls often travel with their parents on their volunteer trips for SEE and actively assistant in patient diagnosis as well as assisting their parents in surgery. Janak and Preeti both believe this gives the girls a real perspective on their place in the world and helps to bind them as a family unit. The Shahs live in Mumbai, India and run a successful eye surgery practice when they are not volunteering for SEE International. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Novartis)

AKHAND JYOTI EYE HOSPITAL, PATNA, INDIA, 10 SEPTEMBER 2014: Blind boy Dablu Kuma, 8, after Cataract surgery at Akhand Jyoti Eye Hospital, the third largest eye hospital in India. This hospital performs over 65000 last year. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Reportage by Getty Images.)

SHRI BHOJAY SARVODAYA EYE HOSPITAL, BHUJ, KUTCH, INDIA, JULY 22 2015: Dr Janak Shah examines patients after a series of successful eye surgreries. He is an accomplished and prolific eye surgeon who volunteers his services to the global poor via SEE International, an NGO with a focus on curing blindness. He is seen examining patients after he haHe and his wife Preeti are seen examining and performing eye surgery at the Shri Bhojay Sarvodaya Eye hospital close to the India Pakistan border. This is a new hospital that offers modern facilities to SEE where Janak can run a blindness camp as well as perform the surgeries required. Janak graduated from the University of Bombay in 1991, and completed his residency in ophthalmology in 1996. He’s been volunteering with SEE International as an eye surgeon since 1996, and in 2013, passed the milestone of 100 SEE expeditions. He is SEE’s most prolific doctor and has worked in places like the Peruvian Jungle, Gaza Strip, Lebanon, Mongolia, China, Brazil and many other remote locations. He has worked all over India and has performed thousands of eye surgeries, addressing every kind of illness. Janak is a proud adherent of the Jainism religion; he is a strong believer in their religious tenants of mankind being one. Janak often works with his wife Preeti, herself a talented eye surgeon. Together they are a formidable force and can work quickly on a multitude of surgeries in a single day. They have two daughters, one of 11 and the other 15. Both girls often travel with their parents on their volunteer trips for SEE and actively assistant in patient diagnosis as well as assisting their parents in surgery. Janak and Preeti both believe this gives the girls a real perspective on their place in the world and helps to bind them as a family unit. The Shahs live in Mumbai, India and run a successful eye surgery practice when they are not volunteering for SEE International. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Novartis)

WEST BENGAL, INDIA 28 OCTOBER 2013: Anita and Sonia Singh explore the beginning of sight as they walk through bullrushes close to their village after undergoing eye surgery. Both Anita, 5, and her older sister Sonia, 12, are born into poverty with congenital cataract blindness and they will need to excercise their new eyes for at least six months before their sight approximates normal. The surgery to cure cataract blindness is simple and takes 15 minutes but because of the level of poverty in this family they have been unable to pursue the necessary operation. India has more than 12 million blind, the majority of which suffer from cataract blindness. Poverty is the main reason these millions of people are trapped in this condition. Donor funding has recently enabled both sisters to finally go for this operation. This essay is an attempt to tell the story of their lives before surgery, during the operation to regain their sight and after as they begin to discover light.

OMARURU, NAMIBIA, 4 November 2015: Dr Helena Ndume, 54, winner of the Mandela prize and Namibia's most celebrated opthmalogist and a genuine surgeon to the people. Ndume grew up in political exile and studied in East Germany and after the wall came down did her specialisation in West Germany. She has spend many years in government hospitals and performed thousands of eye surgeries, the vast majority of which were for the poorest demographic in Namibia. She is seen outside the remains of the first hospital in Omaruru, where she is currently holding a blindness clinic for people from all over Western Namibia. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Reportage for National Geographic Magazine.)

LORYRA, SOUTH OMO, ETHIOPIA, DECEMBER 2007: Images of the Dassanech people in the Lower Omo Valley, South West Ethiopia, 14 December 2007. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Getty Images.)

OMARURU, NAMIBIA, 2 November 2015: Dr Helena Ndume, winner of the Mandela prize and Namibia's most celebrated opthmalogist, performs cataract surgery on patients attending a blindness clinic in Omaruru, Namibia. Most of these people will recover a degree of sight that has been lost to them for a few years and they are grateful for the opportunity to see again. These camps are held all over Namibia and subsidized by a mix of government funding and donor equipment. They tend to cater to sections of the population that do not receive regular eye care, mostly as a result of poverty. The applicants are screened and if the diagnosis is a mature cataract, they are selected as candidates for a simple operation which in fifteen minutes lends signicant sight to their world. The cataract is removed by a surgical vacuum and a new lens in inserted. Bandages are removed the next day and in most cases a real improvement in vision is the result. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Reportage for National Geographic Magazine.)

OMARURU, NAMIBIA, 2 November 2015: Dr Helena Ndume, winner of the Mandela prize and Namibia's most celebrated opthmalogist, performs cataract surgery on patients attending a blindness clinic in Omaruru, Namibia. Most of these people will recover a degree of sight that has been lost to them for a few years and they are grateful for the opportunity to see again. These camps are held all over Namibia and subsidized by a mix of government funding and donor equipment. They tend to cater to sections of the population that do not receive regular eye care, mostly as a result of poverty. The applicants are screened and if the diagnosis is a mature cataract, they are selected as candidates for a simple operation which in fifteen minutes lends signicant sight to their world. The cataract is removed by a surgical vacuum and a new lens in inserted. Bandages are removed the next day and in most cases a real improvement in vision is the result. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Reportage for National Geographic Magazine.)

OMARURU, NAMIBIA, 31 OCTOBER 2015: Elderly patients, all with mature cataract blindness, await and undergo surgery at a clinic for the blind held at Omaruru District Hospital, Namibia. These camps are held all over Namibia and cater to sections of the population that do not receive regular eye care, mostly as a result of poverty. The applicants are screened and if the diagnosis is a mature cataract, they are selected as candidates for a simple operation which in fifteen minutes lends signicant sight to their world. The cataract is removed by a surgical vacuum and a new lens in inserted. Bandages are removed the next day and in most cases a real improvement in vision is the result. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Reportage for National Geographic Magazine.)

An eye camp for impoverished rural people on the Angolan/Namibian border run by SEE International and Mandela Award winner, Dr Helena Ndume

An eye camp for impoverished rural people on the Angolan/Namibian border run by SEE International and Mandela Award winner, Dr Helena Ndume

An eye camp for impoverished rural people on the Angolan/Namibian border run by SEE International and Mandela Award winner, Dr Helena Ndume

An eye camp for impoverished rural people on the Angolan/Namibian border run by SEE International and Mandela Award winner, Dr Helena Ndume

An eye camp for impoverished rural people on the Angolan/Namibian border run by SEE International and Mandela Award winner, Dr Helena Ndume

An eye camp for impoverished rural people on the Angolan/Namibian border run by SEE International and Mandela Award winner, Dr Helena Ndume

An eye camp for impoverished rural people on the Angolan/Namibian border run by SEE International and Mandela Award winner, Dr Helena Ndume

An eye camp for impoverished rural people on the Angolan/Namibian border run by SEE International and Mandela Award winner, Dr Helena Ndume

An eye camp for impoverished rural people on the Angolan/Namibian border run by SEE International and Mandela Award winner, Dr Helena Ndume. Surgeons are seen showing a 103 year old man back to his ward after successful eye surgery for cataracts.

An eye camp for impoverished rural people on the Angolan/Namibian border run by SEE International and Mandela Award winner, Dr Helena Ndume

An eye camp for impoverished rural people on the Angolan/Namibian border run by SEE International and Mandela Award winner, Dr Helena Ndume

An eye camp for impoverished rural people on the Angolan/Namibian border run by SEE International and Mandela Award winner, Dr Helena Ndume

OMARURU, NAMIBIA, 1 NOVEMBER 2015: A blind Damara Nama woman, Theresa Tsamasas, 85, is seen waiting to be screened after arriving from Okombei, a location over 100 kilometers away, at Omaruru District Hospital, Namibia. Theresa lost one eye to a stick when she was a child and now fears for her future as she has lost her only sighted eye to a mature cataract. These camps are held all over Namibia and cater to sections of the population that do not receive regular eye care, mostly as a result of poverty. They are often the result of donor efforts to make the surgery and lenses possible for impoverished communities. The applicant are screened and if the diagnosis is a mature cataract, they are selected as candidates for a simple operation which in fifteen minutes lends signicant sight to their world. The cataract is removed by a surgical vacuum and a new lens in inserted. Bandages are removed the next day and in most cases a real improvement in vision is the result. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Reportage for National Geographic Magazine.)

OMARURU, NAMIBIA, 4 November 2015: An Herero woman waits for her bandages to be removed after undergoing cataract surgery the previous day at Omaruru District Hospital. Most of the people who undergo this kind of eye surgery will recover a degree of sight that has been lost to them for a few years, they are grateful for the opportunity to see again. These camps are held all over Namibia and subsidized by a mix of government funding and donor equipment. They tend to cater to sections of the population that do not receive regular eye care, mostly as a result of poverty. The applicants are screened and if the diagnosis is a mature cataract, they are selected as candidates for a simple operation which in fifteen minutes lends signicant sight to their world. The cataract is removed by a surgical vacuum and a new lens in inserted. Bandages are removed the next day and in most cases a real improvement in vision is the result. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Reportage for National Geographic Magazine.)

OMARURU, NAMIBIA, 4 November 2015: Herero women waits for their bandages to be removed after undergoing cataract surgery the previous day at Omaruru District Hospital. Most of the people who undergo this kind of eye surgery will recover a degree of sight that has been lost to them for a few years, they are grateful for the opportunity to see again. These camps are held all over Namibia and subsidized by a mix of government funding and donor equipment. They tend to cater to sections of the population that do not receive regular eye care, mostly as a result of poverty. The applicants are screened and if the diagnosis is a mature cataract, they are selected as candidates for a simple operation which in fifteen minutes lends signicant sight to their world. The cataract is removed by a surgical vacuum and a new lens in inserted. Bandages are removed the next day and in most cases a real improvement in vision is the result. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Reportage for National Geographic Magazine.)

OMARURU, NAMIBIA, 1 November 2015: Antonia Nuses, 85, greets her grandson Brendon, in yellow hat, with joy after her bandages are removed after cataract surgery. Both of her eyes have now been operated on and she says her sight is greatly improved. She is thrilled to be able to see her grandchildren again and to be able to move around the house and her neighbourhood by herself once more. She says this gives her back a measure of independence, from boiling a cup of tea to cooking and feeling more like herself again. Antonia and her grandson came all the way from Windhoek for this surgery, it is subsidized and they would not have been able to afford the $60,000 Namibian dollars it would cost to have done privately. These camps are held all over Namibia and cater to sections of the population that do not receive regular eye care, mostly as a result of poverty. The applicant are screened and if the diagnosis is a mature cataract, they are selected as candidates for a simple operation which in fifteen minutes lends signicant sight to their world. The cataract is removed by a surgical vacuum and a new lens in inserted. Bandages are removed the next day and in most cases a real improvement in vision is the result. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Reportage for National Geographic Magazine.)

An elderly woman after eye surgery on the Angolan/Namibia border.

OMARURU, NAMIBIA, 4 November 2015: Dr Helena Ndume, winner of the Mandela prize and Namibia's most celebrated opthmalogist, removes bandages from her cataract patients attending a blindness clinic in Omaruru, Namibia. Most of these people will recover a degree of sight that has been lost to them for a few years and they are grateful for the opportunity to see again. These camps are held all over Namibia and subsidized by a mix of government funding and donor equipment. They tend to cater to sections of the population that do not receive regular eye care, mostly as a result of poverty. The applicants are screened and if the diagnosis is a mature cataract, they are selected as candidates for a simple operation which in fifteen minutes lends signicant sight to their world. The cataract is removed by a surgical vacuum and a new lens in inserted. Bandages are removed the next day and in most cases a real improvement in vision is the result. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Reportage for National Geographic Magazine.)

An eye camp for impoverished rural people on the Angolan/Namibian border run by SEE International and Mandela Award winner, Dr Helena Ndume. Patients are seen praising Dr Ndume for her service.

An eye camp for impoverished rural people on the Angolan/Namibian border run by SEE International and Mandela Award winner, Dr Helena Ndume. Patients are seen praising Dr Ndume for her service.